The steps outlined above are part of a growing movement called Urban Mining. Urban Mining is simply the process of reclaiming raw materials from used products, buildings and waste as illustrated below.

Source: R. Cossum and Ian D. Williams, Urban Minig: Concepts, terminology, challenges, Waste Management, 45, 1-3, 2015

Source: R. Cossum and Ian D. Williams, Urban Minig: Concepts, terminology, challenges, Waste Management, 45, 1-3, 2015

It extends landfill mining to the process of reclaiming compounds and elements from any kind of anthropogenic stocks, including buildings, infrastructure, industries, products (in and out of use), environmental media receiving anthropogenic emissions, etc (Baccini and Brunner, 2012; Lederer et al., 2014). The stocked materials may represent a significant source of resources, with concentrations of elements often comparable to, or exceeding, natural stocks.

A smartphone contains around 40 different critical raw materials, with a concentration of gold 25 to 30 times that of the richest primary gold ores. Dismantling around 1 tonne of mobile telephones will gain 300 grams of gold. Virtually 100% of the metals used in these phones can be recovered. Also, urban mining discarded high-tech products produces 80% less carbon dioxide emissions per unit of gold compared with primary mining operations.

With respect to batteries, about 90% of them are lead-based, but nickel-metal hydride, zinc-based and lithium-based batteries can be a significant source of lithium (7,800 tonnes), cobalt (21,000 tonnes) and manganese (114,000 tonnes).

Europe can potentially mine 2 million tonnes of batteries per year.

Europe’s end of life vehicles represent a large source of secondary base metals such as steel (213 million tonnes), aluminium (24 million tonnes) and copper (7.3 million tonnes), as well as platinum and palladium used in car catalysts.

Increasingly, vehicles also contain large amounts of critical raw materials due to electronics, as well as alloying elements used in steel, aluminium and magnesium. Few electric vehicles have yet reached end of life. With sales rising, these will be a source of growing importance for secondary raw materials like neodymium, lithium and cobalt in the future.

Vehicles: An increasingly rich source of critical raw materials!

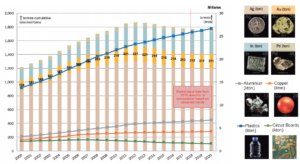

The results of Urban Mining can be seen in the image below. The entire stock of electronic products constitutes a considerable, and for some materials, rapidly changing Urban Mine for the years 2000 to 2020 (last 5 years projected). The figure displays for the first time the combined effect of rapidly increasing sales in numbers of electronic products, increasing miniaturisation of printed circuit board volumes and products appearing (like tablets) and disappearing (like cathode ray tubes) from the market. Plastics and aluminium content are increasing, copper and gold are stabilising, and printed circuit board tonnages are in decline.

Urban Mining development for select elements, materials and components, 2000-2020. EU 28+2.

Source: http://prosumproject.eu/sites/default/files/DIGITAL_Final_Report.pdf

Just like it has become more beneficial to generate electricity with solar energy than with fossil fuels, it is becoming cheaper to extract metal via urban mining than from classic mining: generally speaking, recycling requires less energy per produced kilo of metal than primary production of the metal. The role of recycling will continue to increase in critical raw material production.